One of the best organized forces for helping to alleviate poverty in Peru are the

Clubes de Madres, tens of thousands of small groups of women who get together every weekday to cook a big meal and distribute it to their neighbors at cost. Those who work in the kitchen receive free meals for their families, and certain other people who are disabled or have recently given birth are also exempted from payment. The clubs are partially supported by the government with free rice, and occasionally some beans or canned fish. But they have to pay for their own rent and other expenses. One of the biggest expenses is fuel for cooking.

A friend of mine, Martín, who recently graduated from San Marcos University, is serving as a teaching assistant for an anthropology class that decided to do a project investigating a women´s club in Pamplona, a community in southern Lima that sits high above the rest of the city. Martín knew of my interest in building energy-saving devices and asked if I could help them come up with ways to conserve fuel. They currently spend almost $20 per week on gas for cooking, which represents a large percentage of their variable costs. If they could achieve substantial savings on gas, they could afford to cook more nutritious meals, containing more meat and green vegetables. Or they could afford to buy the materials to build an oven, which would allow them to expand their offerings to generate more income.

A few days ago I spent a morning with six women at their

comedor watching everything they do to prepare the meal, to get some ideas about what interventions help them to reduce gas consumption. They started out with these ingredients:

33 pounds of potatoes

44 pounds of olluco (similar to potatoes)

33 pounds of rice

7 pounds of pumpkin

7 pounds of onions

7 pounds of sémola (wheat-based thickener)

3 pounds of carrots

2 pounds of tomatoes

2 pounds of garlic

9 pounds of chicken feet

1 whole chicken (7 pounds)

They spent most of the four hours peeling and chopping the olluco and potatoes, and one woman spent more than an hour picking through the rice to remove impurities. They cooked in three huge pots. In one they made a soup of the chicken feet, pumpkin, carrots, and spinach. In another they cooked the rice after sauteing some garlic. In the last they cooked the chicken with onions and spices, and then added the olluco and potatoes. It was delicious, but not very nutritious, consisting almost entirely of carbohydrates and fat. Imagine serving more than 100 people with a main dish made from one chicken!

Based on what I observed, I think that placing a ¨pot skirt¨ of galvanized steel around the pots while they cook would help to conserve heat and reduce gas use, and using a ¨retained heat cooker¨ (essentially a box lined with styrofoam) after bringing the rice to a boil would allow the rice to finish cooking without consuming gas. I´ll start to build these next week after the students finish their initial interviews with the women.

We finally jumped through the last two hoops of the bureaucratic procedures for establishing a public water access in San Genaro. The water utility required that we obtain written permission from the municipality to block the road for the period of time necessary to make the connection. The municipality chose to approve it for the period December 18 to 22, so unfortunately I won´t be around for the inauguration and celebration. But Freddy invited me and some of the neighbors to his house for dinner a few days ago, and they presented me with a little gift for my efforts -- a retablo (a Nativity scene in three parts, enclosed in a wooden box).

We finally jumped through the last two hoops of the bureaucratic procedures for establishing a public water access in San Genaro. The water utility required that we obtain written permission from the municipality to block the road for the period of time necessary to make the connection. The municipality chose to approve it for the period December 18 to 22, so unfortunately I won´t be around for the inauguration and celebration. But Freddy invited me and some of the neighbors to his house for dinner a few days ago, and they presented me with a little gift for my efforts -- a retablo (a Nativity scene in three parts, enclosed in a wooden box).

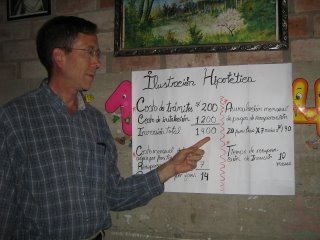

I decided a few weeks ago to set up a small research and development workshop so that volunteers could carry on developing the energy- and money- saving technologies that I´ve been working on. Miguel, my landlord, graciously agreed to let me use part of the big room below my apartment that was being used for storage. I´ve been outfitting it with tools and equipment for working with wood, metal, styrofoam, etc., and instruments for conducting experiments, like a gas flowmeter, balance and thermometer. Yesterday we had the formal opening of the workshop with a half-day class. Only about half of the people who said they were interested in attending actually showed up, but there were at least two, Lucy and Olivia, who are planning to volunteer in the workshop.

I decided a few weeks ago to set up a small research and development workshop so that volunteers could carry on developing the energy- and money- saving technologies that I´ve been working on. Miguel, my landlord, graciously agreed to let me use part of the big room below my apartment that was being used for storage. I´ve been outfitting it with tools and equipment for working with wood, metal, styrofoam, etc., and instruments for conducting experiments, like a gas flowmeter, balance and thermometer. Yesterday we had the formal opening of the workshop with a half-day class. Only about half of the people who said they were interested in attending actually showed up, but there were at least two, Lucy and Olivia, who are planning to volunteer in the workshop.